BIBLICAL COURSE DESIGN MODEL

Introduction to Biblical Foundations of Faith and Learning

Step 1: Create a Concept Map.

- “What is the essential over-arching concept of my course?”

- “How is this concept a truth about God?” and

- “What biblical examples of this concept can be shared meaningfully throughout this course?”

The answers to these questions are used to begin the development of the Course Concept Map. The map streamlines the professor’s thinking and outlines the essential course concept and its spiritual connection, the biblical examples, and the declarative and procedural content of the course, along with assessments that will be used to measure the student’s grasp of the content. Arrows will show relationships between and among the items.

Determining a course concept is the beginning. When the professor focuses students’ attention to the deeper understanding of the major course concept, students will begin to think deeper. At first, it may be hard to believe all the content will still be covered, but the content will be, because professors will learn to prioritize which content is essential. They will also be moving students to a deeper level of thinking, focusing on the higher levels of the revised Bloom’s Taxonomy: analyzing, evaluating, and creating.

To begin, the professor identifies two to three concepts that represent the essence of the course. See Table 2 for a list of suggested major course concepts. Then, brainstorming with colleagues, the professor determines which concept is most essential and best fits the course content. Next, the authors suggest the professor spend time in prayer and reflection on these concepts before determining which one becomes the major course concept and best represents the truth of God and the biblical foundation upon which to build the course.

|

Table 2: Partial List of Major Course Concepts |

|

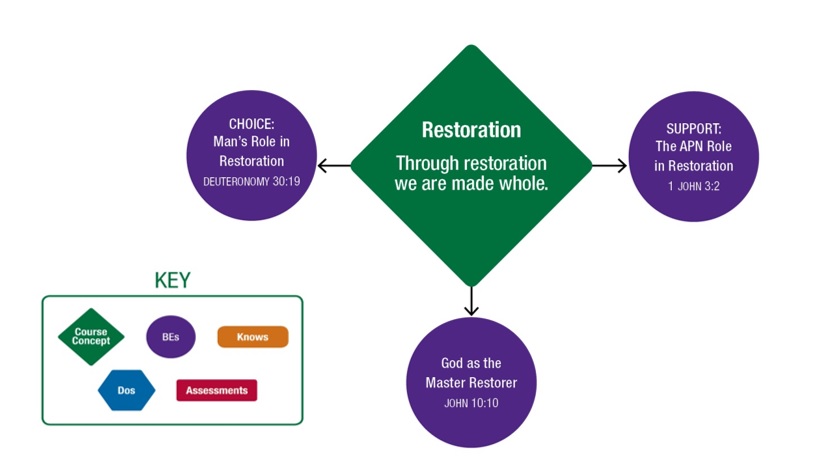

The professor then moves forward to express the major course concept and its spiritual connection in one sentence. For example, a professor teaching NRSG 728: Introduction to Lifestyle Therapeutics identified “Restoration” as the major course concept because the essential concept of the course is restoration of health or living a healthy lifestyle. The professor then made a spiritual connection to “restoration” and to the unique Seventh-day Adventist biblical foundation by stating the relationship in one sentence: “Through restoration we are made whole.” The major course concept and spiritual connection sentence were placed in a green diamond geometric shape in the center of the Course Concept Map, and the map was started. Figure 1 shows the beginning of the Course Concept Map.

Step 2: Write the Learning Outcomes.

LOs describe in sentence form what students are able to demonstrate in terms of knowledge and skills upon completion of the course. The LOs are designed to intentionally show the progression of the learning process and to move students toward higher-order thinking levels. One Learning Outcome (LO) is written for each of the Knows and Dos.

When writing the LOs, the professor should focus on student learning (behavior), and they should be stated in clear, measurable, and observable terms. Vague words, such as understand, know, and become familiar with, are difficult to measure and should be avoided. Instead, the professor should choose action verbs from the revised Bloom’s Taxonomy such as perform, identify, describe, explain, and demonstrate. LOs are written utilizing action verbs from the revised Bloom’s taxonomy to emphasize the development of higher-order critical thinking skills (Anderson et al., 2001). Foundational courses, or General Education courses, will utilize more verbs from the lower levels of the revised Bloom’s taxonomy—remembering, understanding, and applying—whereas upper-division courses will use more verbs from the higher levels—analyzing, evaluating, and creating.

Table 3 shows the Learning Outcomes for NRSG 728. Notice how each of the Learning Outcomes (LOs) correlates directly to one of the Knows or Dos and how each LO is written beginning with an active verb from the revised Bloom’s Taxonomy.

|

Table 3 NRSG 728 Learning Outcomes |

|

Upon successful completion of this course, and through use of a wide variety of instructional technologies in the teaching/learning process, the student will be able to:

|

Step 3: Plan for Feedback and Assessment.

Designing a Feedback and Assessment Plan (FAP) is the third step in the design process and will become part of the course syllabus. Drafting a FAP is an essential tool for the professor. The assessment and feedback plan emphasizes an approach to teaching where assessment is frequent and varied and provides student feedback to improve future student performance. The FAP serves as a reminder of when grading and teacher feedback should be expected, distributing the accountability between the professor and students. It outlines the student and professor engagement throughout the duration of the course. The FAP includes due dates for all assignments and assessments (papers, projects, performances, etc.) and the dates and types of feedback that should be expected from the professor. If the Course Concept Map developed in Step 1 is properly completed, there should already be a preliminary plan for assessing each LO. The Feedback Plan should tell students how they can receive additional feedback from the professor if desired. Feedback is an important part of the FAP and is often overlooked by professors. Clearly outlining when and how feedback will be provided is essential for millennial students.

Constructive feedback is crucial for student learning. The professor should make sure to “close the assessment loop” for most assignments by providing student feedback within 24-48 hours. Ideally, this closure allows students to utilize the professor’s input to improve learning in subsequent class activities and assignments (Nichols & Nichols, 2005). If feedback for a large assignment will take longer than 48 hours, students should be alerted by stating the expected return date in the syllabus and reminded again when the assignment is collected.

Frequent assessment throughout the course is important, so both formative (ongoing, low-stakes) and summative (final) assessments should be included in the FAP. To make the assessment a valuable learning tool, professors should provide a rubric for each major assignment. Ambrose et al. (2010) stated, “Rubrics can be used as scoring or grading guides and to provide formative feedback to support and guide ongoing learning efforts” (p. 231). Adding rubrics to the syllabus strengthens the FAP and allows students to know upfront what to expect, which millennial learners appreciate.

Step 4: Select your Teaching and Learning Activities.

Active teaching and learning activities (T/LA) include a wide range of strategies which share the common element of involving students in doing things and thinking about the things they are doing (Bonwell & Eison, 1991). Active T/LA should be identified and used to engage students in thinking critically or creatively and reflecting upon the learning process to increase their learning. It is important for professors to identify the fundamental skills and thought processes of the content and develop activities that require students to think about and analyze problems using the most powerful theories of the discipline. The professors must present opportunities for students to apply and use skills needed to think like professionals in the discipline. Students need to see the connections between the major course concept, class assignments, BEs, and real world vocational requirements. Vocational examples also need to be connected to the Seventh-day Adventist biblical foundations so students see how Christian behavior is evidenced within the discipline.

The professor begins by identifying a collection of active teaching strategies and deciding which ones can best be used to facilitate the LOs written for the course. Professors should focus on strategies that help students think critically and develop cognitive abilities.

There are many online resources for locating active teaching and learning strategies for use in the higher education setting. A good collection of T/LAs are available at: http://www.umn.edu/ohr/teachlearn/tutorials/active/strategies/ (accessed 1/21/2015). As professors identify and choose which T/LAs to use, the unique needs of the millennial students enrolled in the course and best practices for how to keep them engaged should be taken into consideration. If possible, professors should plan for assignment options and letting students make choices about which activities to complete.

Step 5: Check for Alignment.

To complete the Biblical Foundation Curriculum Design process, the professor should make sure LOs, T/LAs, and assessments are aligned. The professor will check to see that there is an activity and/or assignment, as well as an assessment for every LO. There are other areas to consider: Are some LO’s addressed more frequently than others? Is it appropriate to address some more frequently than others? Critical LO’s need to be revisited often throughout the semester while others are more basic and will require less emphasis. Then, the alignment path should be followed: Every T/LA should align to a LO, and every LO should align to a Know and Do, and every Know and Do should be assessed. Finally, the BEs which are natural connections to Biblical Foundations of Faith and Learning and the major course concept should be reflected and aligned to the Knows and/or Dos. Once the course is designed, the professor is ready to develop a detailed course syllabus, which reflects the requirements of Southern or another Seventh-day Adventist Institution of Higher Education where the professor is employed.

© Robert Overstreet and Elaine Plemons from the Center for Teaching Excellence and Biblical Foundations of Faith and Learning at Southern Adventist University

Course Concept Map Examples

Figure 1

Next, in the creation of the course map for NRSG 728, the professor identified biblical examples (BEs) that related to the course concept. In the example of NRSG 728, the professor identified three BEs. The first BE was found in John 10:10, in which John identifies God as the Master Restorer. The second BE was found in Deuteronomy 30:19, in which man is given the power of choice. The last BE identified was 1 John 3:2, in which John describes the final restoration in man when Jesus comes again. (It is important to note that, if in other semesters this course were taught by different professors, those professors may see the course differently, and another professor will likely find additional or even different biblical examples for the concept of restoration.) The professor put each of the BEs in a separate purple circle and connected, with arrows, each of the BEs to the major course concept on the concept map. Figure 2 shows the BEs added to the concept map for NRSG 728.

Figure 2

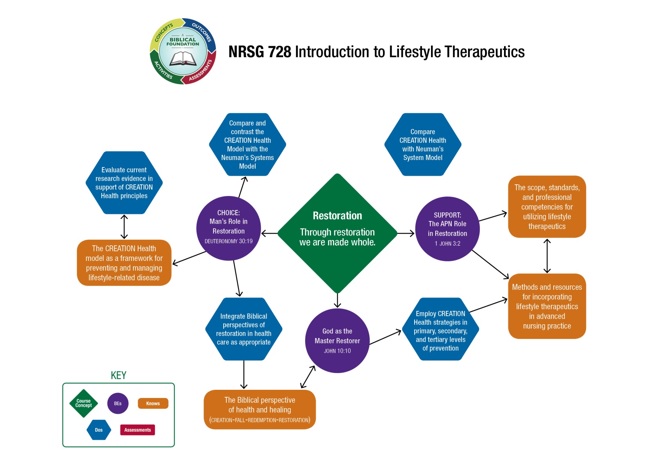

The Biblical Foundation Course Design Model, like McTighe and Wiggins’ (2004) Backward Design Model, emphasizes the identification of the desired end results for the course. The professor must determine which enduring understandings are desired and also determine what academic knowledge students will need to know and what processes students will need to be able to do to demonstrate understanding of the course content. The professor listed the academic knowledge (Knows) and the processes (Dos) for the course. (Note that the Dos are procedural steps in learning, not an assessment or an assignment.) The professor placed each Know in an orange rectangular shape and each Do in a blue hexagon shape and added them to the edges of the concept map.

The Knows and Dos will later be transcribed into Learning Outcomes, utilizing verbs from the revised Bloom’s Taxonomy. It is important to note that this model emphasizes the development of students as critical thinkers. Therefore, as the Knows and Dos are identified, the professor will begin thinking about how adding the verb to the LOs will help students advance to higher levels of critical thinking, such as analyzing and evaluating the content and creating new information utilizing the academic content.

The professors looking back again at the Biblical Examples already identified should determine where the BEs make the best connection to a Know or a Do. At this point in the process, the BEs are usually rearranged on the Concept Map to a position closer to the Know or Do where they best connect, and an arrow is drawn connecting the BE to the appropriate Know and Do. Figure 3 shows the Concept Map with the Knows and Dos added for NRSG 728.

Figure 3

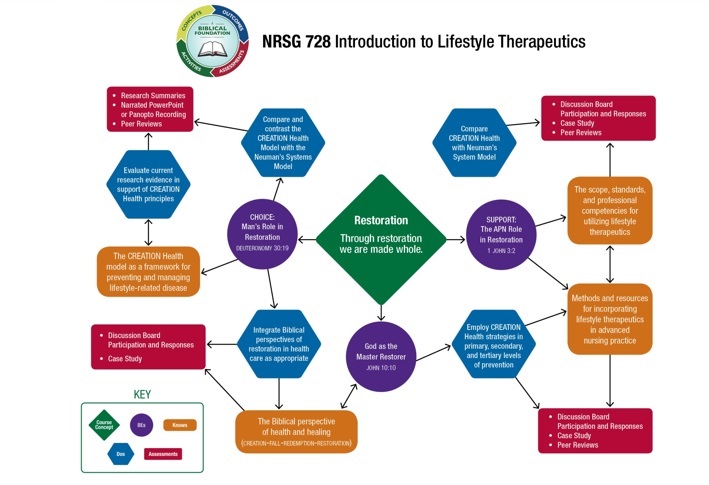

To complete the Concept Map the professor determined which assessments measure student understanding of each Know and Do. She used the Knows and Dos to determine the acceptable evidence that demonstrated students’ mastery of the content. She then placed the assessments in red rectangular shapes and connected each shape to the appropriate Know or Do. Carefully crafted, one assessment may connect to more than one Know or Do. The professor utilized real-world activities or projects for these assessments whenever possible. In the NRSG 726 example, she decided to use case studies, discussion boards, peer reviews, research summaries, and a narrated PowerPoint or video recording as her assessments for the Knows and Dos in her course. She did not rely solely on quizzes and tests, which are low-level assessments and should not be the only type of assessment used in the course. Figure 4 shows the Concept Map for NRSG 726 with the assessments added and the connections of the assessments to the Knows and Dos.

Figure 4

The completed Course Concept Map shows the major course concept connected to the BEs, the BEs to the Knows and Dos, and the Know and Dos connected to the appropriate assessments. Then, the next step is to write Learning Outcomes for the course. As stated earlier, these Learning Outcomes will be recorded in the course syllabus so students understand what will be expected of them as they complete the course.

Summer Institute Learning Outcomes

As another example, the Course Concept Map and the Learning Outcomes for the Summer Institute are also given.

The student will be able to:

Design or Redesign a course following the Southern Conceptual Framework.

Generate several connections between the identified Course Concept and their Christian Worldview/Biblical Foundations of Faith and Learning.

Determine which active teaching and learning activities they will put into practice throughout the semester to involve students.

Discuss and/or critique with colleagues various aspects of the Summer Institute requirements.

Understand the needs of millennial students and create a classroom environment which meets those needs.

Plan to use technology tools which will enhance the learning for millennial learners.